Recently a writing friend of mine, Kathy George (you can find her on her blog, Dappled With Dew) approached me with a request. Kathy is an accomplished writer whose manuscript, Sargasso, is currently under consideration by Hachette. Kathy asked if I’d like to participate in a blog-hop which was set up by a friend of hers, Bec Jessen. The idea is that each week a new writer posts their answers to questions about their writing process, then introduces another writer who has agreed to follow them. As I love finding out about the practice of other writers, of course I said yes.

The writer who will follow me is Les Zigomanis. He has had stories and articles published in various print and digital journals and his novel, Just Another Week in Suburbia, was selected for the 2013 Hachette Manuscript Development Program. At the moment he is currently working on a new novel, House of Cards, as well as blogging weekly about his journey with neurosis at http://www.leszig.com.

And now, here is my contribution to the ongoing writers’ questionnaire:

What are you working on at the moment?

Right now I’m close to finishing the second of what I hope will be a trilogy of historical novellas set on Stradbroke Island (Minjerribah) in the 1860s. The first one, True Story Man, was written white hot in five weeks (though it’s had numerous drafts since then). The one I’m on now, the sequel titled Truth is Green, was also going full steam ahead until I hit a brick wall. I was faced with the crucial moment in the plot and was shocked by the violence in the scene I had so happily planned. Just couldn’t think how to write it. But thankfully, five months later, the novella is back on track.

I’ve also been collaborating with a writer friend, Kathy George, in an exercise designed by Brian Kiteley which I discovered online. The idea is that one writer provides the opening lines, three or four sentences usually, then the other takes it up, and so on until the story gets exciting. At this point Kathy and I retire to create our own fiction. The results so far have been astonishing ‒ not only are we producing interesting work, but I at least have written stuff I could never have imagined writing before: the first a ghost story, the second a gritty tale about a paedophile. The intriguing aspect to this exercise is its serendipity, the way each other’s input dovetails in surprising ways with the themes we later devise. No doubt it’s just the creative process at work ‒ some Freudian synthesis of disparate elements ‒ but to me it is simply magical.

How do you think your work differs from that of other writers in your genre?

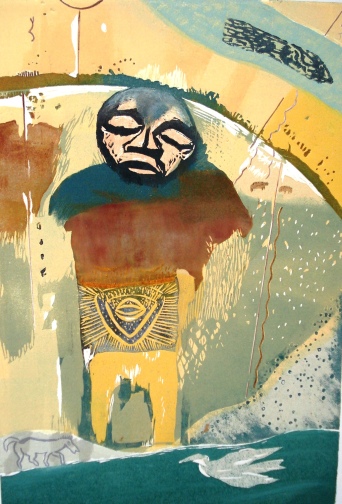

I work mainly in historical fiction and like all serious writers in this genre, that means a huge amount of research. So nothing different there. Probably where I depart from existing models is in my choice of subject, which has a strong Indigenous angle. Not exactly politically correct these days, a white writer presuming to depict the ‘other’, but in my view the history of racial conflict in Australia, particularly its initial struggles, lies at the heart of who we are as individuals and as a nation.

2014 Stradbroke Island

Why do you write what you write?

In a recent debate on the pros and cons of speaking for the other, featured in Overland magazine, Stephanie Convery gave a brilliant defence of the right, if not duty, of white writers to ‘fly in the face of identity politics’ by representing Indigenous people, and I couldn’t put my answer any better than she did.

She argued, among other things: ‘There are powerful progressive Indigenous writers working on Indigenous issues in Australia and they should be read widely. But allies of marginalised peoples have responsibilities, too. If the progressive response by white writers is not to say or do anything at all, then the relationship between Indigenous activism and white progressives has a dismal future.’ That’s exactly how I feel, that we have a responsibility to contribute to the depiction of racism, to critique power structures rather than allow them to go unchallenged by putting the subject in the too-hard basket. It was no accident that the inspiration for starting my first novella, True Story Man, was the desire to ‘write back’ to The Tempest, Shakespeare’s archetypal play about the coloniser and the colonised.

The above is not to say my novellas are pedantic, because they’re not. They’re lively enough and contain humour because they’re intended to entertain, not preach.

What’s your writing process and how does it work?

In my case it’s get up early and write. That’s the first thing. By mid-afternoon my brain is duller. The best stuff always gets done in the morning. I write directly onto the word processor and I like quiet. When I’m painting I find music helps, but for writing, silence and seclusion work better. When a long story or novel is in full swing I find the night teems with words. They fizz and pop and I have learned to keep a notebook beside the bed. When I need to clarify ideas or resolve difficult passages, I find it’s useful to take a walk. So, sometimes, is lying on my back on grass, looking up at the sky.

Despite current advice to the contrary, I’m not a writer who just ‘gets it down’ regardless of quality, and keeps forging on. It has to be pretty well word perfect before I move on. I used to worry about this perfectionist trait, but have since read accounts by well known writers who describe working in the same way.